When it comes to volcanoes, the biggest fear is not if they’ll erupt…but when. Even when we think those fiery fiends are dead and buried, an alarming number of dormant volcanoes have been known to rise from the grave and threaten our very existence.

While the world’s biggest active volcano is Hawaii’s Mauna Loa, that’s dwarfed by the (hopefully) extinct Tamu Massif in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

This year has seen volcanoes dominate the news alongside all the other apocalyptic foreshadowings, and if it’s not Mount Spurr threatening to rain devastation onto the capital of Alaska, it’s Russian earthquakes potentially triggering a deadly ‘Ring of Fire’, or Hawaii’s Kīlauea volcano shooting lava 1,000 feet into the air.

The likes of Mount Etna, Stromboli, and Yellowstone all have their time in the spotlight, but according to the University of Birmingham’s Professor Mike Cassidy, it’s the silent assassins we need to be keeping an eye on.

The volcanologist told The Conversation that these ‘hidden volcanoes’ are especially dangerous because they’re not being monitored like the above. Highlighting supposedly dormant volcanoes in regions including the Pacific, South America, and Indonesia, Cassidy reiterates that eruptions from volcanoes with no recorded history happen every seven to ten years.

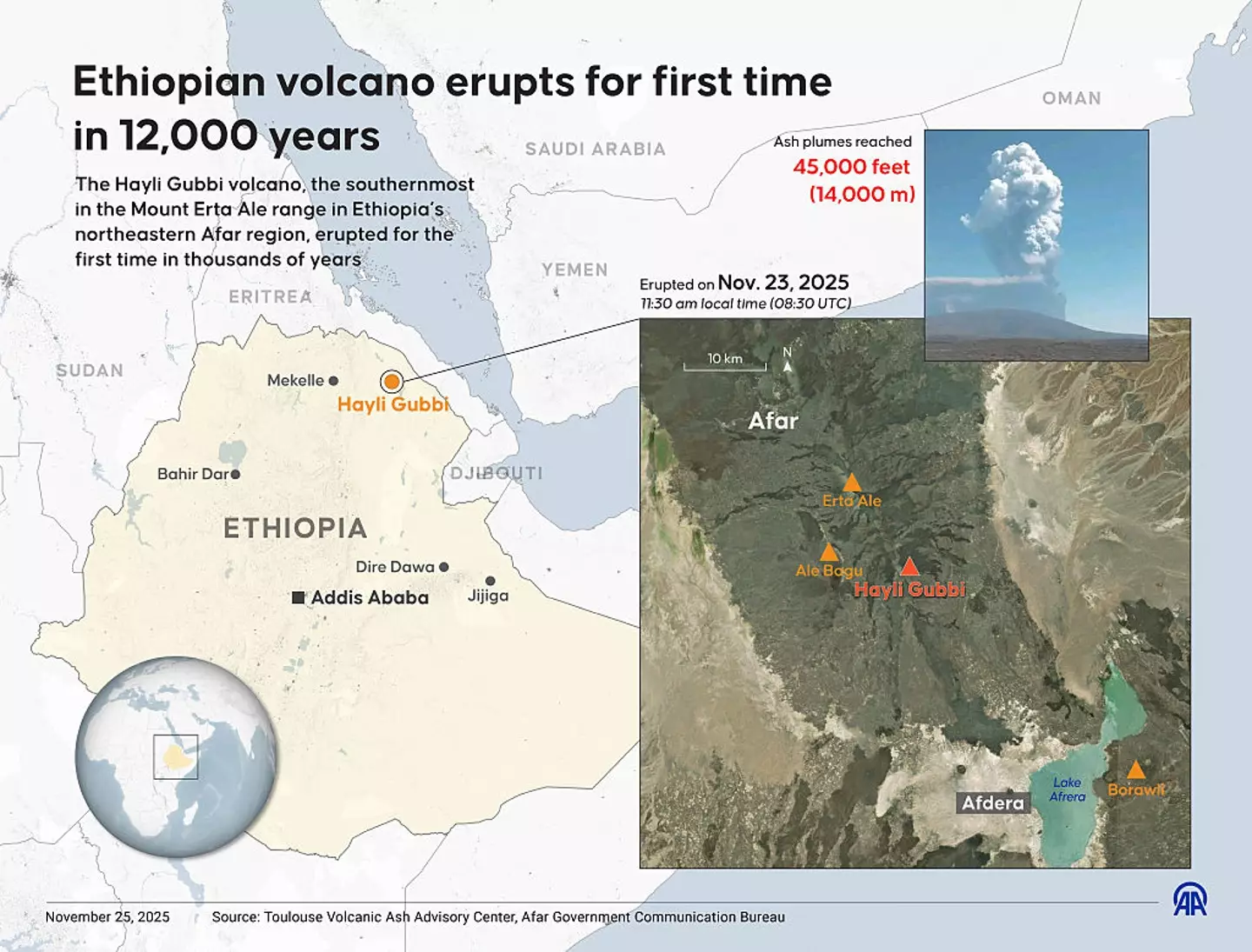

He points to the November 2025 eruption of Hayli Gubbi in Ethiopia, which has been quiet for 12,000 years but just unleashed widespread chaos. As Hayli Gubbi popped its top, ash plumes soared 13.7 kilometers into the sky and debris spanned two continents as ash fell into Yemen and Indian airspace.

Hayli Gubbi has caused widespread destruction (Anadolu / Contributor / Getty)

Flights had to be cancelled, but in the grand scheme of things, this is nothing compared to what these hidden volcanoes can really do.

The outlet reports on the 1982 eruption of Mexico’s El Chichón after it lay dormant for centuries.

With the scientific community caught off guard, El Chichón threw ash as far as Guatemala, over 2,000 people died, and 20,000 were displaced.

Even worse than this, it’s said the volcano’s sulphur deposits created reflective particles in the upper atmosphere, which cooled the northern hemisphere and shifted the African monsoon toward the south to cause a severe drought.

Despite history attempting to teach us a lesson, it’s thought that less than half of all active volcanoes are monitored. Even then, research is disproportionately focused on the most famous ones.

It’s so skewed, there are more reports just on Etna than there are on the combined 160 volcanoes of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vanuatu.

Alongside his colleagues, Cassidy has launched the Global Volcano Risk Alliance. The charity aims to raise “anticipatory preparedness for high-impact eruptions” by working with scientists, policymakers and humanitarian organisations while highlighting “overlooked risks, strengthen monitoring capacity where it is most needed, and support communities before eruptions occur.”

As we wrongly assume that what is quiet will remain quiet, Cassidy says that acting early is imperative.

Remembering that three-quarters of all eruptions come from volcanoes that have been dormant for at least 100 years, the Global Volcano Risk Alliance wants to improve monitoring across the board.

Saying that efforts need to be shifted to Latin America, south-east Asia, Africa, and the Pacific, Cassidy concluded: “This is where the greatest risks lie, and where even modest investments in monitoring, early warning and community preparedness could save the most lives.”